Done right , the smart platform for infrastructure planning and execution could lead to tremendous productivity benefits.

Shyam Ponappa | November 2, 2022

The National Master Plan for logistics development on a digital platform, Gati Shakti (Speed and Strength), was introduced in October 2021. It is a much-needed initiative to introduce effective management systems in coordinating relevant ministries for all aspects of transportation and logistics. It establishes digitised institutional processes for comprehensive, integrated project planning and execution, to assist ministries and infrastructure sectors in achieving results. The aims are more efficient outcomes at reduced cost and time. Done correctly, this will result in tremendous productivity benefits at a low cost and with better environmental impact.

A primary purpose of Gati Shakti is prioritisation for growth. Based on limited lay access (more on this later), an element that needs attention is telecommunications reform. The need is for inexpensive, higher capacity/intensity connectivity, by enabling spectrum usage for wireless and shared networks at lower capital investment with better utilisation. The platform’s effectiveness depends on this.

Gati Shakti is based on the recommendations of the National Transport Development Policy Committee1 in January 2014. Government agencies such as the railways, roads and highways, shipping, aviation, power, telecom, and so on reportedly use this for integrated planning and execution. During the past year, ministries responsible for fertiliser, coal, ports and the like reportedly identified nearly 200 “infrastructure gaps” in first-mile or last-mile logistics. An inter-ministerial expert panel monitors and recommends corrective action. Presumably, this will be tracked through the digitised database and portal, which also has geographic positioning capabilities.

Prioritisation And Policy Changes More Essential Than Capital

As observed in an earlier column, a World Bank study across many countries validates the importance of telecommunications (and electricity) for growth.2 A report published by the Asian Development Bank Institute confirms that for India and China, internet and mobile density contribute to their high rate of growth.3

Apart from these findings from past data, telecommunications and digitisation are now essential to most aspects of living. Most importantly, telecommunications and the internet need major policy changes on network sharing and reduced taxes. These are needed even more than capital, to accelerate network coverage and delivery. Examples of changes required include permitting high-speed wireless without loading discretionary costs, such as up-front auctions, high costs for wireless links, and onerous procedures. Policy changes can reduce pricing and sticky process/procedures for operators and, ultimately, users and society as a whole. Until this is done, users are either deprived of services because they are simply not there, or constrained by erratic and low-quality services, or burdened with high charges. The impact is in many areas as indicated below:

- Environmental care & climate mitigation: Effective broadband coverage and shared networks significantly improve both.

- Education and work life reach: Extending broadband coverage to the many millions living in rural or distant areas is one obvious need. This is also true for the many urban users who endure poor services, beyond the privileged, relatively few who have fibre or reliable high-speed wireless. Undoubtedly, a whole gamut of content and methods will need to evolve to enable effective learning for less educated users, as will ways to mitigate costs to provide access. But it is probably the only way crucial services can reach so many quickly, channel our population productively and pre-empt their degeneration into disruptive problem creators. This will open education to many more boys and girls, and employment opportunities to men and women.

- Similar benefits are feasible in areas such as e-commerce, distributed healthcare, government services, in small and medium manufacturing and services enterprises for work process support systems, and entertainment.

Temples to Metaphysics and Physics

In the 1890s, Acharya Jagadish Chandra Bose (Sir Jagadis Chandra Bose) demonstrated wireless technology at 60 GHz (V-band),4 but his pioneering work languished in India. Meanwhile, countries such as the USA, the UK and others, including China, have exploited this technology for high-speed gigabit wireless in their networks in place of fibre.

Much time and public resources are devoted to overt religiosity in India. Whereas Bose, scientist extraordinaire, in his inaugural address dedicated the Bose Institute in Kolkata in 1917 as not merely a laboratory but a temple. Adding Paramahansa Yogananda’s “keen interest in evidence that India can play a leading part in physics, and not metaphysics alone”, we would do well to apply more physics and science—as in using wireless technology in our networks, and having more temples to science, systems, and other practical disciplines.

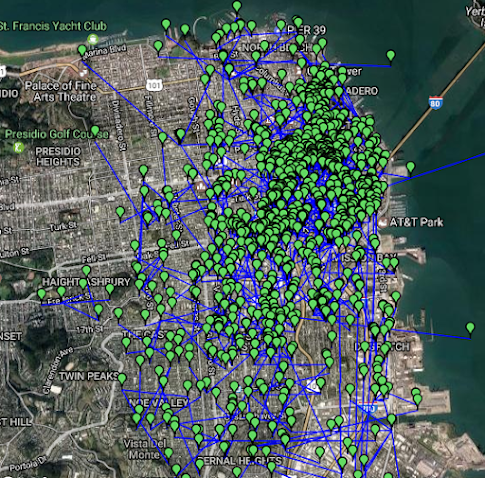

India has just enabled restricted use of 60 GHz, although devices were available abroad for years. If government permits telcos to use 60 and 70-80 GHz “mmWave” technology for pay-for-use backhaul with no loading of extraneous costs (auctions, extra taxes), there would be enormous service and cost benefits in India, as in San Francisco and London (see the device maps in the charts for one supplier).

V-Band and E-Band Devices in San Francisco and London for One Vendor (2017)

Figure 3: Siklu radios in San Francisco, CA, according to FCC database

Source: https://go.siklu.com/blog/custom-blog/the-evolution-of-mmwave-2

Figure 5: Siklu radios in London, UK, according to OFCOM database

Source: https://go.siklu.com/blog/custom-blog/the-evolution-of-mmwave-2

Changes are also needed to institutionalise easier access to spectrum for authorised institutions and researchers, so that India’s research and development for commercial and defence is freed of arbitrary, self-imposed constraints and delays.

Public access to the Gati Shakti portal, limited for security reasons, was allowed from October 2022. A cursory look at the portal does not disclose project details on sectors. It may be more amenable to authorised users; to a lay user, it appears to be a repository of reports that does not cater to meaningful queries or logical searches. Adding such capabilities would make it more informative and useful, although this will need to be balanced with security.

The essential points are that improving living conditions requires enabling and applying technology and know-how. Attention to scientific and domain applications to deal with ground realities will help improve our state of infrastructure for productivity and ease of living. Prioritising digitisation and telecommunications will help correct losing out on growth and associated living conditions because of inappropriate policies, and genuinely add both Gati and Shakti to our efforts.

1:

India Transport Report

Moving

India To 2032

Vol

I - Executive Summary

National

Transport Development Policy Committee, January 31, 2014

Rakesh

Mohan et al

Summary

Recommendations: http://www.aitd.net.in/NTDPC/rep_ntdpc_v1.pdf

2:

How Much Does Physical Infrastructure Contribute to

Economic Growth?

An Empirical Analysis

Govinda Timilsina, David I.

Stern, Debasish K. Das

World Bank Group, Development

Economics

December 2021

https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/36780

3: Digitalization and Economic

Performance of Two Fast-Growing Asian Economies: India and The People's

Republic of China

Dukhabandhu Sahoo, Suryakanta

Nayak, and Jayanti Behera

ADB Institute Working Paper

Series

No. 1243

March 2021

4:

Jagadis Chandra Bose: Millimetre Wave Research in the Nineteenth Century

Darrel

T. Emerson

National

Radio Astronomy Observatory

949

N. Cherry Avenue, Building 65

Tucson,

Arizona 85721

1998

https://www.cv.nrao.edu/~demerson/bose/emerson_delhi.pdf